Experiments in the Terraform Test framework, Part I: Plans

by Alex Harvey

A while back I raised an Issue #21628 in the Terraform project suggesting that a real unit test framework is needed for Terraform, and I was delighted to hear that HashiCorp is about to ship one in the forthcoming Terraform v1.6.0. I had written a blog post at the time on an early feature branch idea. But something much cleaner than that prototype has emerged in the alpha version of the framework, and, in this post, I document some of my experiments so far with it.

Tests can be written in the HCL language on both plans and real infrastructure. I have split the blog post up into two parts therefore, this first part being about testing plans, and the second part about testing real infrastructure using apply.

From what I can see, so far, version 1.6 of Terraform is a big leap forward in terms of having a properly testable infrastructure-as-code in Terraform. I am, personally, very excited about this!

- Code and resources

- Project structure

- Simplest example

- Test locals

- Expecting failures

- Known after apply

- Conclusion

- Refs

Code and resources

If you’d like to follow along, the source code for all of my tests are here.

Project structure

Everything about this framework is nice and simple, and that’s true of the project structure. No configuration is required. All you have to do is create a ./tests directory, put some test files in it, and run terraform test. Some TF files for your module are expected to be in the top level of the project as usual. Here is my initial set up:

% tree .

.

├── main.tf

└── tests

└── test_main.tftest.hcl

Notice the file extensions there. Instead of .tf — Terraform HCL files — the extension is .tftest.hcl. These are HCL files that look a lot like Terraform code, although actually use a custom HCL language specific to this testing framework. Also, the test files are required to have this file extension, or else they will not be discovered by the terraform test command.

Simplest example

The first thing I did was a simple “hello world” to get my head around the simplest example of a test.

variable "word1" {

type = string

}

variable "word2" {

type = string

}

locals {

hello = "${var.word1}, ${var.word2}!"

}

output "message" {

value = local.hello

}

This is artifically simple code that has a couple of variables, combines them in some text interpolation in a local variable, and emits a message as an output.

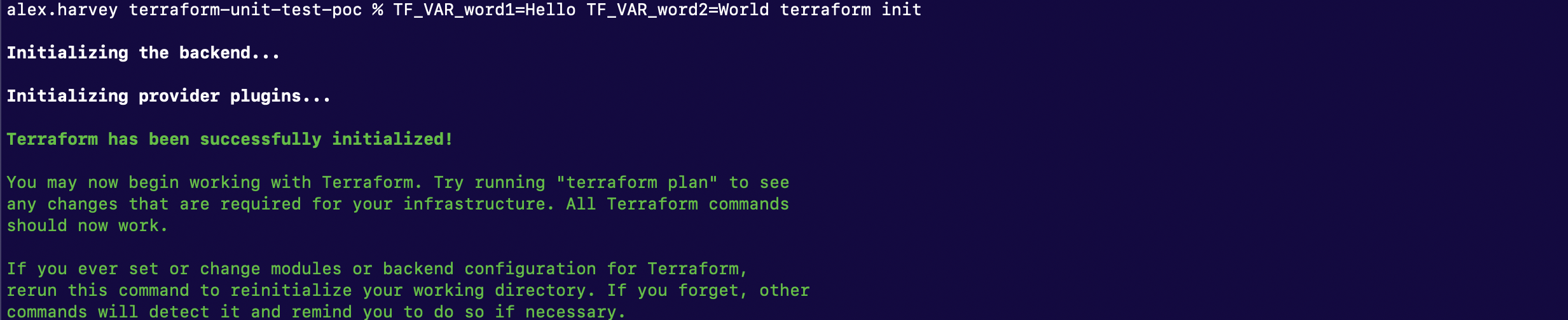

Let’s try init and plan on that:

And:

Notice here what is available in the plan outputs. Since the plan has an output, I can write an assertion about the plan’s output. Here’s my first test:

variables {

word1 = "Hello"

word2 = "World"

}

run "test_output" {

command = plan

assert {

condition = output.message == "Hello, World!"

error_message = "unexpected output"

}

}

A few notes about the grammar here:

- We have a

variablesblock that allows me to set the values of the input variables. Notice that this is not the same syntax as in a Terraformvariabledeclaration, and this syntax would not work in Terraform itself. - Notice that the

variablesblock is at the top-level and not inside therunblock. More on this below. - We then have a

runblock that names a test case. People familiar with other unit test frameworks might be surprised that this block is namedrunand not saytestas it would be in PyTest, jUnit and so on. But that’s ok. Just note thatrundeclares a named test case. - Inside the

runblock we have thecommandattribute. This can be eitherapply(default) orplan. - An

assertblock where I define a test case condition and an error message for when the test fails. Again, quite similar toassertin other languages like Python. - Finally, a real gotcha: Note carefully the syntax

output.message. This won’t work in Terraform itself, as outputs can’t be referred to inside a module like this (and the syntax for referring to them outside is different too).

Ok, let’s run the test:

Although not visible from my screenshot, these tests ran quite quickly. Of course, in this example, there are no providers to download and the code is extremely simple. Still, I’m pleased that this is a fast test.

Test locals

Let’s change the code so that we have a more complicated expression — something a bit more complex that you might actually want to test.

variable "list_of_words" {

type = list(string)

}

locals {

upper_cased = [for s in var.list_of_words : upper(s)]

}

Now I have one of Terraform’s Python-like list comprehensions and these are not always trivial or readable. Sometimes, it would make sense to have test cases to test these for a range of inputs. Let’s do that.

variables {

list_of_words = ["foo", "bar", "baz"]

}

run "test_some_words" {

command = plan

assert {

condition = local.upper_cased == ["FOO", "BAR", "BAZ"]

error_message = "unexpected output"

}

}

run "test_empty_list" {

variables {

list_of_words = []

}

command = plan

assert {

condition = length(local.upper_cased) == 0

error_message = "unexpected output"

}

}

And this works too:

So, notice here how you can define variables at the top level, and then override them in the test cases. This will be quite convenient in a real world module where there are many variables and the differences between test cases is likely to be one or two variable values.

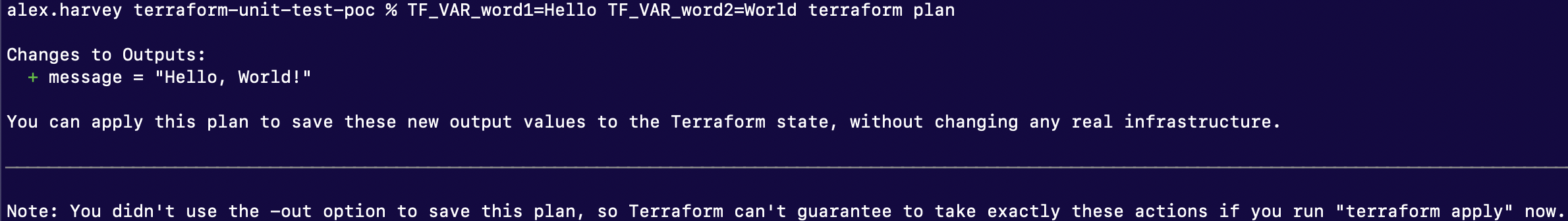

A gotcha though. It turns out that you can’t (as yet, anyway) do this:

run "test_some_words" {

variables {

list_of_words = ["foo", "bar", "baz"]

}

command = plan

assert {

condition = local.upper_cased == ["FOO", "BAR", "BAZ"]

error_message = "unexpected output"

}

}

run "test_empty_list" {

variables {

list_of_words = []

}

command = plan

assert {

condition = local.upper_cased == []

error_message = "unexpected output"

}

}

This code errors out as follows:

Still, there’s some very useful functionality here.

Expecting failures

In the next example I have some more complex code that filters on some data. I’d also like to show how to expect failures, and test for invalid inputs.

variable "projects" {

description = "Map of projects"

type = map(object({

region = string

environments = list(string)

}))

validation {

condition = alltrue([

for proj in var.projects : (startswith(proj.region, "us-east-") || startswith(proj.region, "ap-southeast-"))

])

error_message = "The provided region for some projects is unexpected. It should start with 'us-east-' or 'ap-southeast-'."

}

validation {

condition = alltrue([

for proj in var.projects : alltrue([for env in proj.environments : contains(["dev", "tst", "uat", "sit", "stg", "prd"], env)])

])

error_message = "Some environments in the projects are invalid. They should be one of: 'dev', 'tst', 'uat', 'sit', 'stg', or 'prd'."

}

}

locals {

ap_southeast_region = [

for key, val in var.projects : key

if startswith(val.region, "ap-southeast")

]

us_east_region = [

for key, val in var.projects : key

if startswith(val.region, "us-east")

]

}

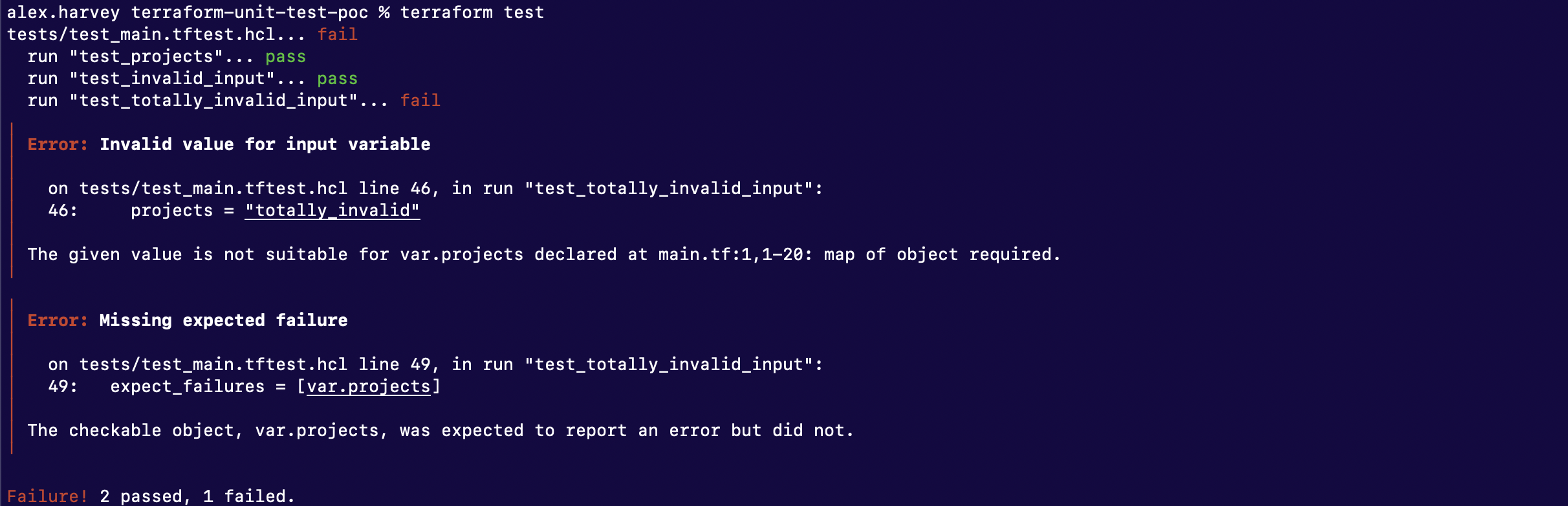

And to test this I try to pass in various examples of valid and invalid data 1:

variables {

projects = {

customer_api = {

region = "ap-southeast-1"

environments = ["dev", "uat", "prd"]

}

internal_api = {

region = "ap-southeast-2"

environments = ["prd"]

}

payments_api = {

region = "us-east-1"

environments = ["dev", "tst", "uat", "sit", "stg", "prd"]

}

}

}

run "test_projects" {

command = plan

assert {

condition = local.ap_southeast_region == ["customer_api", "internal_api"]

error_message = "unexpected projects in ap-southeast"

}

assert {

condition = local.us_east_region == ["payments_api"]

error_message = "unexpected projects in us-east"

}

}

run "test_invalid_input" {

variables {

projects = {

customer_api = {

region = "eu-west-1"

environments = ["dev", "uat", "prd"]

}

}

}

command = plan

expect_failures = [var.projects]

}

Notice that in the second test case, I expect failures.

I must admit this is the most confusing aspect of the framework that I have found so far. Initially, I had hoped that expect failures might be more like Python’s ‘assert raises’ — that is, something that could catch Terraform erroring-out for any reason at all. Sadly, no.

The use case for expect_failures is much more specific. It is based on the custom conditions for a given resource, data source, variable, output or check block.

In the example here therefore, I expect the validation to fail for var.projects because I have a validation that ensures that my regions start with us-east- or ap-southeast-.

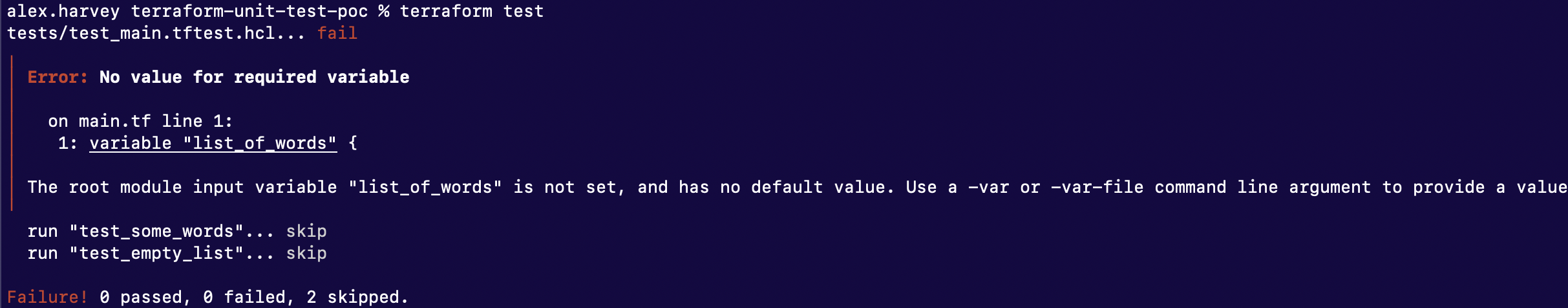

But now let’s see what happens when I pass in data that is of an unexpected type:

run "test_totally_invalid_input" {

variables {

projects = "totally_invalid"

}

command = plan

expect_failures = [var.projects]

}

This test now fails when I hoped that it would pass:

So the bottom line is there does not appear to be any way of simply trapping all failures yet.

Known after apply

The examples so far have been a little contrived in that I have not called on any of the Terraform Providers to configure any actual resources. In this last example therefore, I use the Random Provider to show what it looks like to test plans on real providers.

It is important to realise that when testing plans that would configure resources, assertions about resource attributes that are known after apply cannot be tested in the plan; you would need to create the real infrastructure before you can make assertions about many of their attributes. More on this in Part II of this blog post on testing apply.

The code example I have is this one:

variable "len" {

type = number

}

resource "random_id" "id" {

byte_length = var.len

}

Ok, that is really simple. I have a random ID of configurable length. (The Random ID resource might be used for example to create a pseudo-random string to be used as part of an S3 bucket name.)

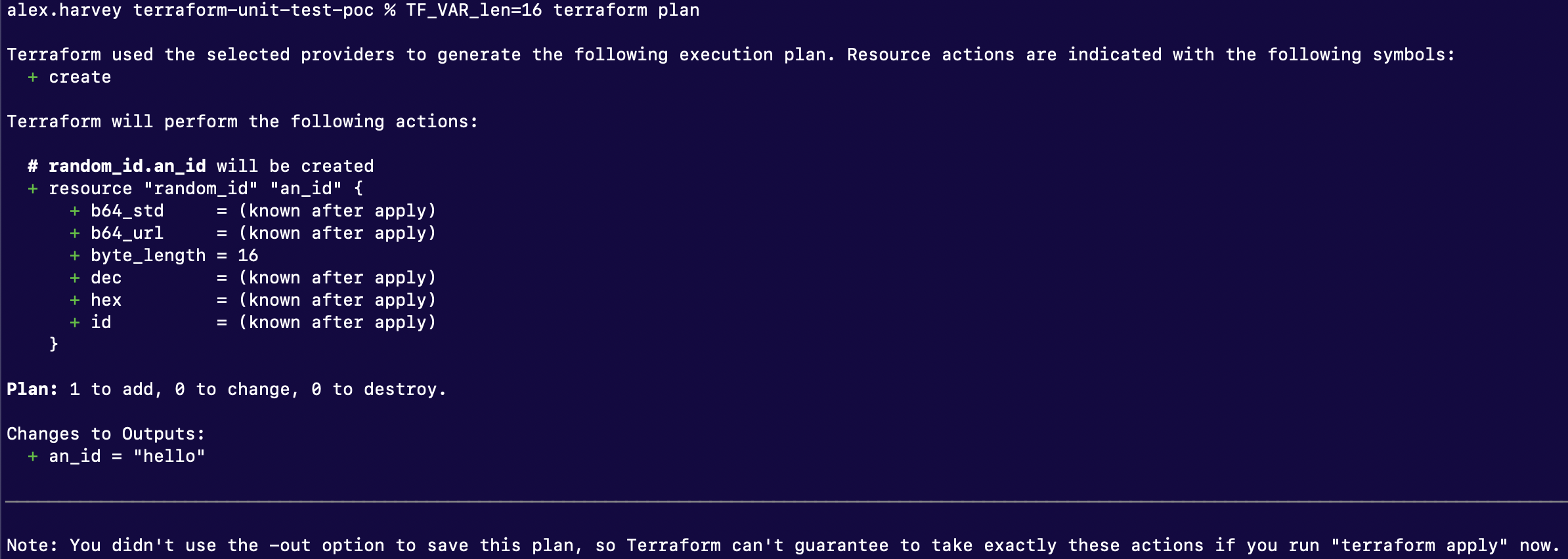

In order to write assertions about the plan here, I realised quickly that it makes sense to start by running terraform plan so as to see what is available. Here goes:

Here I can see that most things are known after apply, whereas in my plan, I can see that the byte length is known. Thus, I could make a test like this:

variables {

len = 16

}

run "test_len" {

command = plan

assert {

condition = random_id.id.byte_length == 16

error_message = "expected byte length"

}

}

In this simplified example, that might seem kind of pointless. And I would agree, don’t write tests for the sake of writing tests, but use them for the sake of testing something that needs to be tested. In Terraform, it is the complicated expressions, functions, conditional logic and iteration that is often hard to read that really needs to be tested, and this framework makes available all of the locals, outputs and resource attributes that will depend on the complex logic, giving us a lot of flexibility to test what we need to test.

I’m excited!

Conclusion

I have enjoyed testing out Terraform’s new test command on plans. Tests on plans can be fast, easy to write and understand, and make it possible to test Terraform’s complex logic so as to give us real confidence in our infrastructure-as-code.

I do notice that the default for the command has been set to apply and not plan. This tells me that HashiCorp’s developers see tests on apply as being the real value add here, and the tests that most people will want to write. I tend to agree with that, because DevOps engineers as a community have been slow to understand and embrace unit testing, perhaps due to many lacking a background in real software development.

For myself, I don’t want to write slow and expensive tests that create real infrastructure, if I can test my complex logic without doing that. So I always prefer to have more unit tests and fewer end-to-end tests on real infrastructure. But both are needed, and in the next part I am going to look at how to test apply.

Refs

- Terraform 1.6.0 Alpha’s unmerged docs on Terraform Test.

- Brendan Thompson,

Terraform For Expressionswhere I borrowed some code examples!