Configuration management with Troposphere and Jerakia

by Alex Harvey

This post documents a proof of concept using Troposphere and Jerakia for managing AWS Cloudformation stacks.

- Overview

- Disclaimer

- The problem

- High level design

- Why the puppet conventions

- Code solution

- Todo

- Conclusion

- Further reading

Overview

This idea came out of a hack-a-thon of sorts. Here, I document an idea for configuration management of AWS resources as Cloudformation stacks with proper data handling and secrets management. The idea uses the Troposphere library to write out Cloudformation templates; and Jerakia as an external data store, which can integrate with tools like Hiera EYAML or Hashicorp Vault for secrets. In the Python code, I have adopted the conventions from Puppet, with Python classes instead of Puppet classes; Troposphere calls that resemble Puppet resource declarations; and Jerakia lookups that are similar in form to Hiera parameter lookups.

Disclaimer

As mentioned, the idea came out of a single day of hacking, so it is not something I have experience with using in production. But with that said, I can’t see any reason why it would not be suitable. Your mileage may vary.

The problem

AWS Cloudformation has many benefits, including a declarative DSL that is easy to understand, change sets that bring visibility of changes prior to deployment, and Lambda-backed custom resources. Cloudformation groups AWS resources together so that they can be managed as units or “stacks”. Recent feature additions like drift detection have made it even more powerful. And more features are added all the time.

The Cloudformation DSL, however, when viewed as a programming language, is limited, lacking basic features like functions, variables, iteration, a standard library, etc, and its data handling is limited to a flat array of parameters. Similarly, there is no way to do unit testing.

For these reasons, many have chosen to use tools like Terraform or the Ansible Cloudformation module as an alternative to Cloudformation. But these solutions have problems too. The DSLs of both Terraform and Ansible are limited. Features like iteration and conditional logic are available, but their implementation is confusing and generally limited when compared to programming languages like Python or Ruby. And Ansible has the additional problem that the Jinja2 template language is needed to interpolate in Cloudformation templates, which introduces other problems.

Terraform is admittedly popular at the moment, although I suspect that its popularity owes more to its superior user experience1 and the solid Hashicorp brand than it does to the flexibility and usefulness of the DSL and its actual fit to the problems it tries to solve. Feature-wise, it is quite comparable to the Puppet 3 DSL and earlier, and it introduces a “state” problem, which is a Terraform-specific problem where infrastructure “state” is tracked that contains information from both the Terraform code you wrote as well as run-time information from the cloud provider.

Terraform’s limitations have already given rise to the Terragrunt project, which has, at the time of writing, 1,879 stars on Github and 57 contributors, and is billed as “a thin wrapper for Terraform that provides extra tools for keeping your Terraform configurations DRY, working with multiple Terraform modules, and managing remote state”. But with Terragrunt and Terraform both in place, there are too many layers of separation between the infrastructure-as-code and the infrastructure for my liking.

The data handling of these solutions is not excellent either. Terraform’s tfvars is limited compared to Puppet’s Hiera and Jerakia. The data store is tightly coupled to Terraform itself, and lacks features like merging of hashes and hierarchical lookups. Ansible’s data handling is also limited.

And finally, neither Terraform nor Ansible has unit testing. As a result, automated testing is generally a slow process that can impact on the team’s velocity in a negative way.

High level design

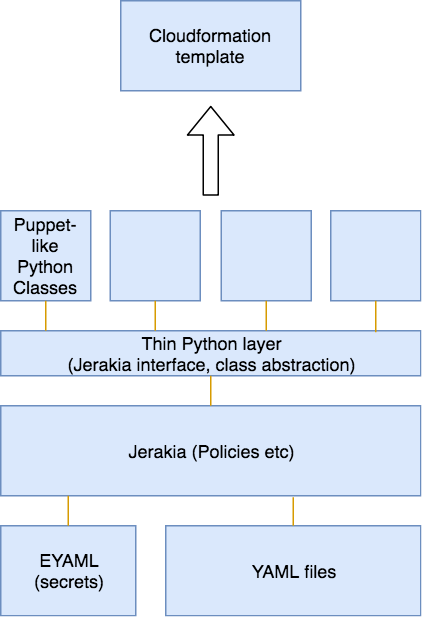

The solution I propose here, as far as I can tell, solves all of these problems. The architecture is shown in the following figure:

Aside from the Troposphere library itself, there is a very thin layer of custom Python code; a pattern of organising classes in a Puppet-like way; and Jerakia as a hierarchical data store. And for secrets, I could have SSM, Hiera-EYAML, Hashicorp Vault etc.

The benefits are:

- Python is a flexible OO-programming language that gives us variables, iteration, conditional logic and other features.

- The Puppet conventions of Roles, Profiles, Modules2, Classes and Resource Declarations is a well-understood, mature pattern of configuration management.

- Jerakia provides a flexible, Hiera-like hierarchical key-value data store.

- The solution gives us a way to manage secrets.

The only disadvantages known to me are:

- Both Troposphere and Jerakia are open source projects not backed by a company at this point.

- Not all AWS resources are supported by Troposphere. So, a willingness to add features to Troposphere may be a requirement for some. This is, of course, true of Terraform as well.

Why the puppet conventions

A reader may wonder why I would adopt the conventions of the Puppet community in a Python project. Well, as far as I can tell, the Troposphere project has not provided any recommendations for the organisation of the Python code; all of the examples are Python scripts without organisation into functions or classes.

Meanwhile, the Puppet conventions evolved for solving configuration management patterns over more than a decade. The Puppet community is the oldest infrastructure as code community, and I think these patterns are the ones that have stood the test of time.

Code solution

Jerakia setup

To set up Jerakia, I created a Gemfile to install Jerakia as a Gem:

source 'https://rubygems.org'

gem 'jerakia'

The Jerakia config file lives in the top level of the project as jerakia.yaml:

---

policydir: ./policy.d

logfile: ./log/jerakia.log

loglevel: info

I created a single default policy in policy.d/default.rb:

policy :default do

lookup :main do

datasource :file, {

format: :yaml,

docroot: './jerakia/data',

searchpath: ['common'],

}

end

end

And then my data files like common.yaml live in ./jerakia/data.

Of course, Jerakia can do many more things that are out of the scope of this simple proof of concept. It is very powerful indeed.

Thin Python Layer

Virtualenv setup

I created a simple Python virtualenv. Firstly, I created a requirements.txt file with just one line:

troposphere

And then I created the virtualenv in the usual way:

virtualenv ./virtualenv

source ./virtualenv/bin/activate

pip install -r requirements.txt

And that of course made the troposphere library available to my code.

Jerakia interface

Jerakia is expected to be run from Bundler, as it is a Ruby project. The Jerakia interface is just a few lines of code:

from subprocess import check_output

import json

import os

class Jerakia:

def lookup(self, key):

os.environ["JERAKIA_CONFIG"] = "./jerakia.yaml"

command = "bundle exec jerakia lookup %s --output json" % key

json_string = check_output(command, shell=True)

return json.loads(json_string)

At some point, this interface may want to be replaced by an external Python library. For the moment, it just calls subprocess.check_output() to Jerakia inside a bundle. My use of the JERAKIA_CONFIG environment variable was to workaround a bug in the Jerakia command line in the version 2.5.0 that was available at rubygems.org.

Troposphere base class

A very small amount of shared Trosophere setup code is abstracted away as the following base class:

from troposphere import Template

class TropBase:

jerakia = Jerakia()

template = Template()

def write(self):

self.build()

print(self.template.to_json())

As can be seen, the TropBase class expects a subclass to implement the build() method. These methods are analogous to Puppet classes.

Puppet-like classes

In the next two sections, I introduce some code that creates a simple EC2 instance with a Key Pair and an output with the Instance ID.

Mappings class

First, I have a class that adds some Cloudformation Mappings. In Puppet’s grammar, I imagine something like this:

class stack::mappings (

Hash[String, Hash] $mappings,

) {

$mappings.each |$region, $ami| {

$ami_id = $ami['AMI']

mapping { $region:

'AMI' => $ami_id,

}

}

}

}

I chose this example to illustrate real iteration, something that doesn’t exist in native Cloudformation, or in Ansible or Terraform. Here, I do something that users of both these languages often wish they could do: simply loop over an array or hash/dict.

In the Python/Troposphere version, I can do exactly the same thing in a Python for loop:

class Mappings(TropBase):

def __init__(self):

self.Mappings = self.jerakia.lookup("Mappings")

def build(self):

for region, ami in self.Mappings.iteritems():

ami_id = ami["AMI"]

self.template.add_mapping("RegionMap", {region: {"AMI": ami_id}})

Then in Jerakia we have data in a YAML file:

---

Mapping:

us-east-1:

AMI: ami-7f418316

us-west-1:

AMI: ami-951945d0

us-west-2:

AMI: ami-16fd7026

eu-west-1:

AMI: ami-24506250

sa-east-1:

AMI: ami-3e3be423

ap-southeast-1:

AMI: ami-74dda626

ap-northeast-1:

AMI: ami-dcfa4edd

Points to note here are:

- The

__init__()contructor is used to initialise the class attributes with lookups from Jerakia. Of course, we don’t have Puppet’s automatic parameter lookup, which means our calls to Jerakia must be explicit, although not everyone in the Puppet community likes the automatic parameter lookup feature, and, certainly, the Python community values explicit over implicit. - The

build()method is comparable to the Puppet class’s body, where resources are declared.

EC2 Instance class

Here is another class that again resembles a Puppet class with resource-like declarations:

class Ec2Instance(TropBase):

def __init__(self):

self.InstanceType = self.jerakia.lookup("InstanceType")

def build(self):

keyname_param = self.template.add_parameter(Parameter("KeyName",

Description = "Name of an existing EC2 KeyPair to enable SSH access to the instance",

Type = "String",

))

ec2_instance = self.template.add_resource(ec2.Instance("Ec2Instance",

ImageId = FindInMap("RegionMap", Ref("AWS::Region"), "AMI"),

InstanceType = self.InstanceType,

KeyName = Ref(keyname_param),

SecurityGroups = ["default"],

UserData = Base64("80"),

))

self.template.add_output([Output("InstanceId",

Description = "InstanceId of the newly created EC2 instance",

Value = Ref(ec2_instance),

)])

We can imagine a Puppet class like this:

class stack::ec2_instance (

String $instance_type,

) {

parameter { 'KeyName':

'Description' => 'Name of an existing EC2 KeyPair',

'Type' => 'String',

}

resource::ec2_instance { 'Ec2Instance':

'ImageId' => 'FindInMap("RegionMap", Ref("AWS::Region"), "AMI")',

'InstanceType' => $instance_type,

'KeyName' => 'Ref("KeyName")'

'SecurityGroups' => ["default"],

'UserData' => 'Base64("80")',

}

output { 'InstanceId':

'Description' => 'InstanceId of the newly created EC2 instance',

'Type' => 'Ref("Ec2Instance")',

}

}

Putting it together

Now to build the stack, I need one more class to put all the classes together in a single template:

class Stack(TropBase):

def build(self):

Mappings().build()

Ec2Instance().build()

Stack().write()

Note here the call to the write() method. The template itself has been shared between all the classes as a class variable - similar to the Puppet catalog? - so that final call to the inherited write() method is all that is required to write out the template as JSON. Or YAML could be used instead if you prefer.

I called the script ec2_instance.py, so a Cloudformation stack can be now created using the AWS CLI this way:

python ec2_instance.py > ec2_instance.json

aws cloudformation create-stack --template-body file://ec2_instance.json

Todo

At this point, I haven’t actually set up the Hiera EYAML library, but I understand it is trivial - just add the hiera-eyaml Gem to Gemfile; follow the instructions for generating keys from the project’s README; and then add a block like this to jerakia.yaml:

eyaml:

public_key: /etc/jerakia/secure/public_key.pem

private_key: /etc/jerakia/secure/private_key.pem

Likewise, I haven’t worked out how I would unit test these classes, although something quite similar to Rspec-puppet would be possible. That is, it should be easy to write assertions that check that given certain data in the inputs, expected Cloudformation templates are written out at the end.

Conclusion

It certainly was fun to set this all up. I have described a setup for using Troposophere and Jerakia for managing AWS Cloudformation stacks as infrastructure as code. I argue that this method has advantages compared to Terraform and Ansible, as it allows us to use Python instead of these more limited DSLs. I also suggested a pattern for organising the code based on the conventions of the Puppet community, which I think are a good fit for infrastructure as code problems.

I have not used this pattern in production yet, and I would welcome any critical feedback.

1 By which I mean the nice output seen when running terraform apply, the readable DSL and so on.

2 Although Python modules are a bit different to both Puppet and Ruby modules. I am not certain at this stage that I would actually use Python modules in the same way.

Further reading

- Paulina Budzon, Using Troposphere to create CloudFormation stack template

- Craig Dunn (@crayfishx), Solving real world problems with Jerakia

- Avi Friedman, The road to infrastructure as code, Part 1

- Yevgeniy Brikman, Terraform tips & tricks: loops, if-statements, and gotchas