Comment on AEMO/CSIRO GenCost 2019-20

by Alex Harvey

The national science agency CSIRO, and energy market operator AEMO, recently posted a draft for stakeholder review of the annual update to last year’s 2018 GenCost report, which had concluded that solar and wind generation technologies are the lowest-cost ways to generate electricity in Australia compared to other new-build technologies.

According to Giles Parkinson, the report:

…confirms that wind, solar and storage technologies are by far the cheapest form of low carbon options for Australia, and are likely to dominate the global energy mix in coming decades.

Over the last few days, I read this report carefully, and found a number of troubling assumptions that led me to seriously doubt its conclusions.

About GenCost 2019-20

The GenCost 2019-20 is an update to GenCost 2018, that provides current LCOE and capital costs for generation and storage technologies, and also projections of future LCOE and capital costs. The current costs however are taken from other reports. The focus of the report therefore is on the projections.

Projection methodology and scenarios

The projection methodology, as noted in the Executive Summary (p. v), assumes that cost reductions in Australia are a function of global technology deployment. Three global scenarios are considered, Central, High VRE, and Diverse.

The Central scenario assumes that existing policies will continue that promote the deployment of renewables as well as a low carbon price. The Diverse and High VRE scenarios assume that a high, and rising global carbon price will be implemented this year, in 2020. The High VRE scenario is then further distinguished from Diverse by the removal of “constraints” on renewables deployment. The following table summarises the key differences in the scenarios:

| Key Drivers | High VRE | Diverse | Central |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon price | High | High | Moderate |

| RE constraints | Removed | not removed | not removed |

| RE Targets | High | 50% | Current |

There are also other differences in the scenarios (see p. 8) although these appear to be the main differences.

Note that the three scenarios appear to be the key methodological departure from GenCost 2018. In GenCost 2018, there are only two scenarios, 4-degrees and 2-degrees, distinguished simply by a low and high carbon price, respectively. I will come back to this.

Dubious assumptions

In the following sections, I look at a number of assumptions in the GenCost 2019-20 draft, that, taken together, should increase the costs of SMR nuclear and decrease the costs of solar, wind and storage.

The global carbon price

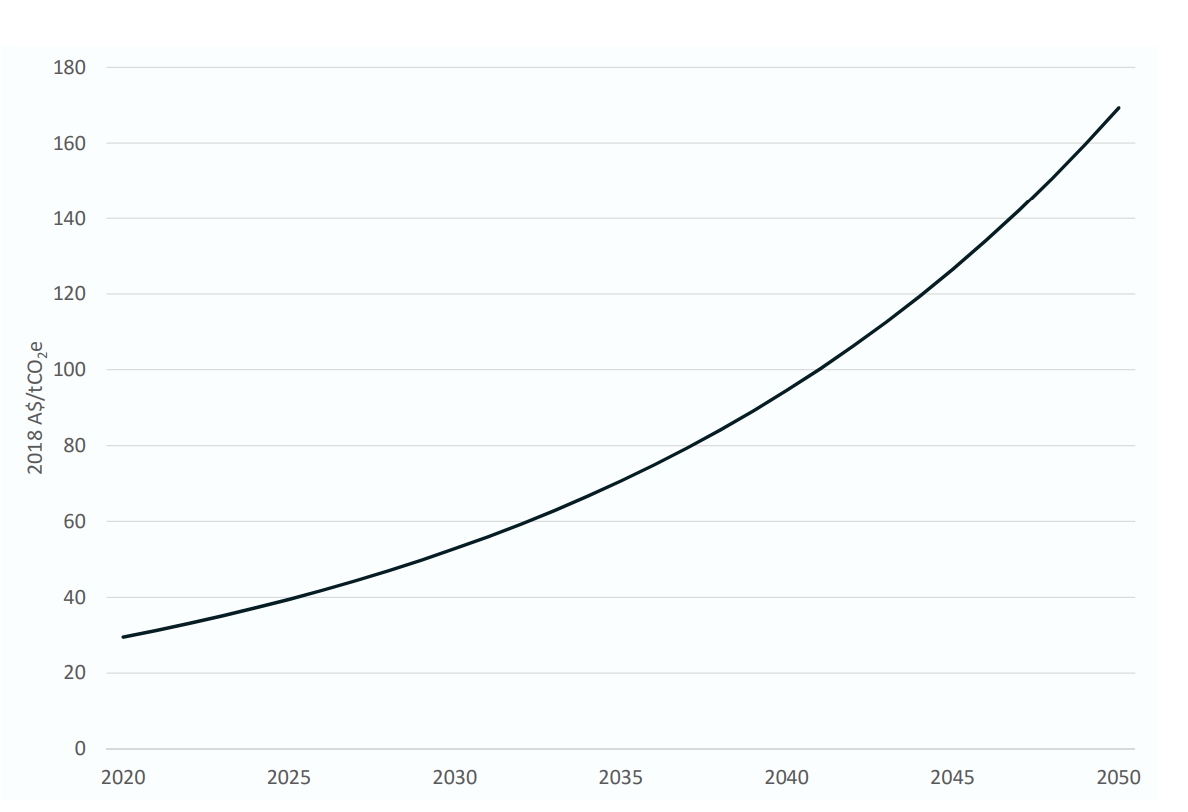

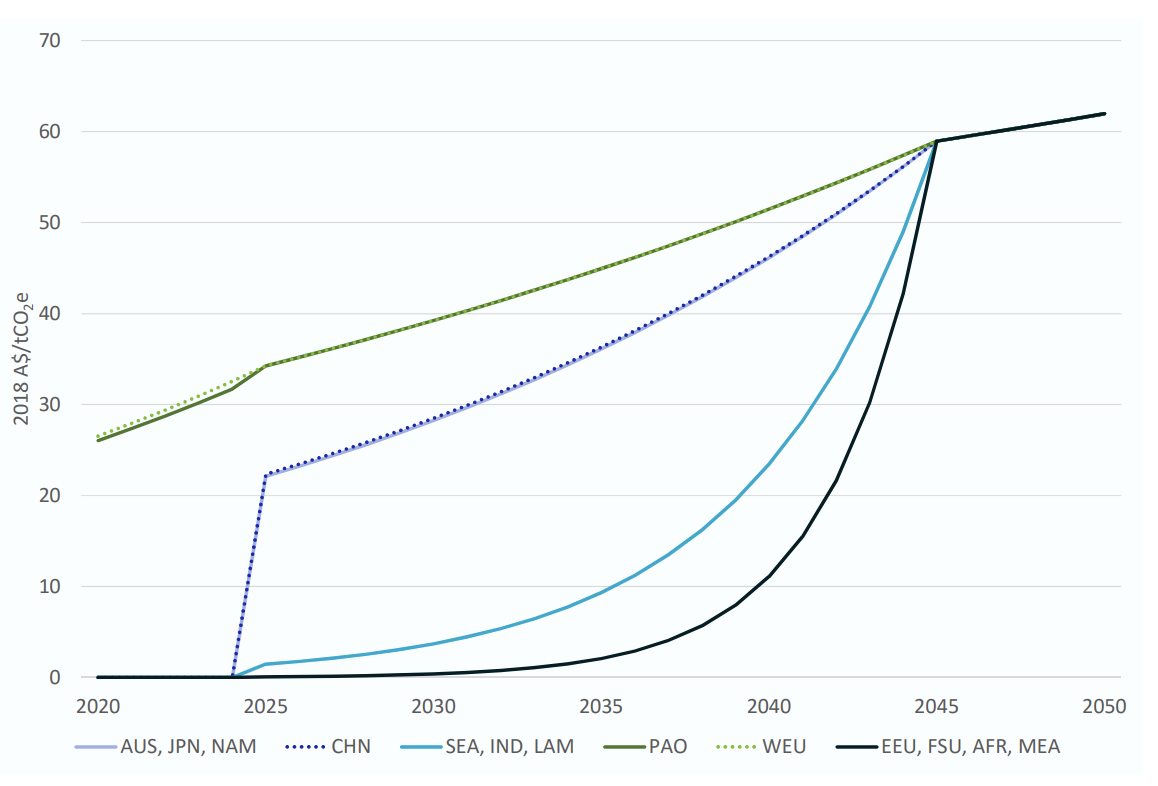

The following charts show the carbon prices used in High VRE and Diverse (Fig. A.2, p. 30) and then in Central (Fig. A.3, p. 31):

It should be immediately apparent that the assumption in High VRE and Diverse of a high, global carbon price of $30/tonne, starting in 2020, is not plausible, considering the outcome at Madrid, the China/US Trade War, and so on. Similarly, a carbon price of $22.5/tonne in China, Japan, and North America (NAM) starting in 2025 seems unlikely too. It may have seemed believable to the IPCC in 2013, although the rise of Xi Jinping in China and Donald Trump in America makes it is a lot less likely now.1

Likewise, there is an assumption of a steadily rising carbon price in the EU in the Central scenario. It is true that, at the time of writing, the EU carbon price is coincidentally around €28/tonne, although it has hovered around €5-10/tonne for most of the last decade. In an optimistic case, it could perhaps rise, per Fig. A.3. But is it “probable”?

Note that the GenCost 2019-20 is explicit that the carbon price is the biggest factor in lowering the price on renewables (p. 29):

GALLME [Global and Local Learning Model for Electricity] contains government policies which act as incentives for technologies to reduce costs or limits their uptake. The key assumption about government policy that has an impact on results is a carbon price.

But what if the major emitters never agree to a carbon price? The objective of GenCost is to provide a realistic cost estimate for a range of technologies, so a range of realistic scenarios should be explored. Should the modelling not include a scenario where the world decarbonises by direct investments in technology like SMR nuclear instead of only by the global carbon price? This also seems consistent with the actual policies adopted in China, India, Russia, Japan and other places.

High VRE and constraints

As noted earlier, GenCost 2018 did not include a High VRE scenario, only a 4-degrees scenario with a moderate carbon price, and a 2-degrees scenario with a high carbon price. In their description of the GALLM model (GenCost 2018, p. 45), the authors wrote about the constraints on VRE in their model:

The optimisation problem includes constraints such as government policies, demand for electricity or transport, capacity of existing technologies, exogenous costs such as for fossil fuels and limits on resources (e.g. rooftops for solar photovoltaics). The models have been divided into 13 regions and each region has unique assumptions and data for the above listed constraints. The regions have been based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD) regions (with some variation to look more closely at some countries of interest) and are: Africa, Australia, China, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, Former Soviet Union, India, Japan, Latin America, Middle East, North America, OECD Pacific, Rest of Asia and Pacific.

The objective function of the model is to minimise the total system costs while meeting demand and all constraints.

And in Appendix A.1.5 (p. 48):

Constraints around the availability of suitable sites for renewable energy farms, available rooftop space for rooftop PV and sites for storage of CO2 generated from using CCS have been included in GALLME as a constraint on the amount of electricity that can be generated from these technologies (Government of India, 2016) (Edmonds, et al., 2013). See (Hayward & Graham, 2017) for more information.

The same text appears in GenCost 2019-20 Appendix A.2.2, but the authors add a note that the resource constraint on renewables was removed in High VRE. There is no further explanation. Similarly, it is mentioned in the table on p. 8 that rooftop PV space is “less constrained”.

So what are the “constraints”? There is more information, by the same authors, in Hayward & Graham, 2017 (p. 4):

While there has for many years been discussion of the potential for new cross-border transmission schemes for accessing high quality renewable resources (e.g. MENA-EU Solar Energy Super Grid; Asia Super Grid), we assume no such schemes are developed during our projection period, due to their great uncertainty. Existing trade via inter-country transmission, such as within the European region, is accounted for.

So, the same authors had previously expressed great skepticism about the idea of removing the constraints. And yet, now, they have removed them anyway, and provided no reason.

The idea of the Asia Super Grid, mentioned here, is favoured by anti-nuclear, 100% renewables advocates, like Mark Z. Jacobson and Mark Diesendorf. The super grid would connect Japan, South Korea, North Korea, Russia, China and Mongolia in an inter-country transmission network. This assumption allowed Diesendorf & Elliston, 2018, for instance, to conclude that land-poor South Korea and Japan could participate in a 100% renewable energy system by using transmission lines from Russia, China and North Korea.

From an engineering point of view, of course, the idea makes a certain amount of sense. But from a geopolitical point of view, it is crazy. There is no way that Japan or South Korea would make themselves dependendent for energy on their authoritarian adversaries.

High VRE and SMR Nuclear

In the GenCost 2018, SMR Nuclear was not included as a separate technology. But in response to advocates of the SMR Nuclear technology, CSIRO and AEMO felt compelled to include it. Noting that SMR Nuclear is a new technology, it ought to enjoy a learning rate similar to other emerging technologies. This led to a significant drop in price for SMR nuclear in 2030, as shown in Fig. 3-8:

So, it can be seen that, if the unrealistic High VRE scenario was not included in the report, the impression of SMR nuclear would be much more favourable. It would have been hard, for instance, for Giles Parkinson, at Renew Economy, to write this:

In virtually every scenario, the CSIRO study envisages a world dominated by wind and solar by 2050. Nuclear may play a slightly increased role in the “diverse technology” scenario, but this is only with artificial limits placed on the deployment of wind and solar.

High carbon price and high renewable energy targets

The purpose of a high carbon price is to be a technology-neutral market incentive to use and develop low carbon energy. Ideally, renewable energy targets would be removed in a world with a high carbon price. This was recommended, for example, in the Garnaut report commissioned by the Rudd government.

In all of the GenCost scenarios, however, the world chooses to adopt both a carbon price and renewable energy targets. In the High VRE, there is a high carbon price, and a high renewable energy target. In Diverse, a high carbon price and lower renewable energy targets. And in Central, all existing renewable energy targets are preserved, as a moderate global carbon price is added.

Naturally, these assumptions tend to lower the price of solar, wind and storage, at the expense of SMR nuclear.

SMR Nuclear and CCS in Central and Diverse

On p. 14 it is noted that the carbon price in the Central scenario is not high enough to warrant investment in nuclear. Meanwhile, in High VRE,

… the model has chosen investment in reducing costs of renewables and gas with CCS as the most efficient solution reflecting abundant renewable resources and greater existing progress on reducing CCS costs.

It is not clear why the model has made this choice. But it raises the question, how realistic is it that gas with CCS would be chosen in the real world? The IEA’s SDS scenario, for instance, uses very little CCS due to low confidence in the technology. Again, it appears that SMR nuclear is locked out by another doubtful assumption.

Battery prices and scarce resources

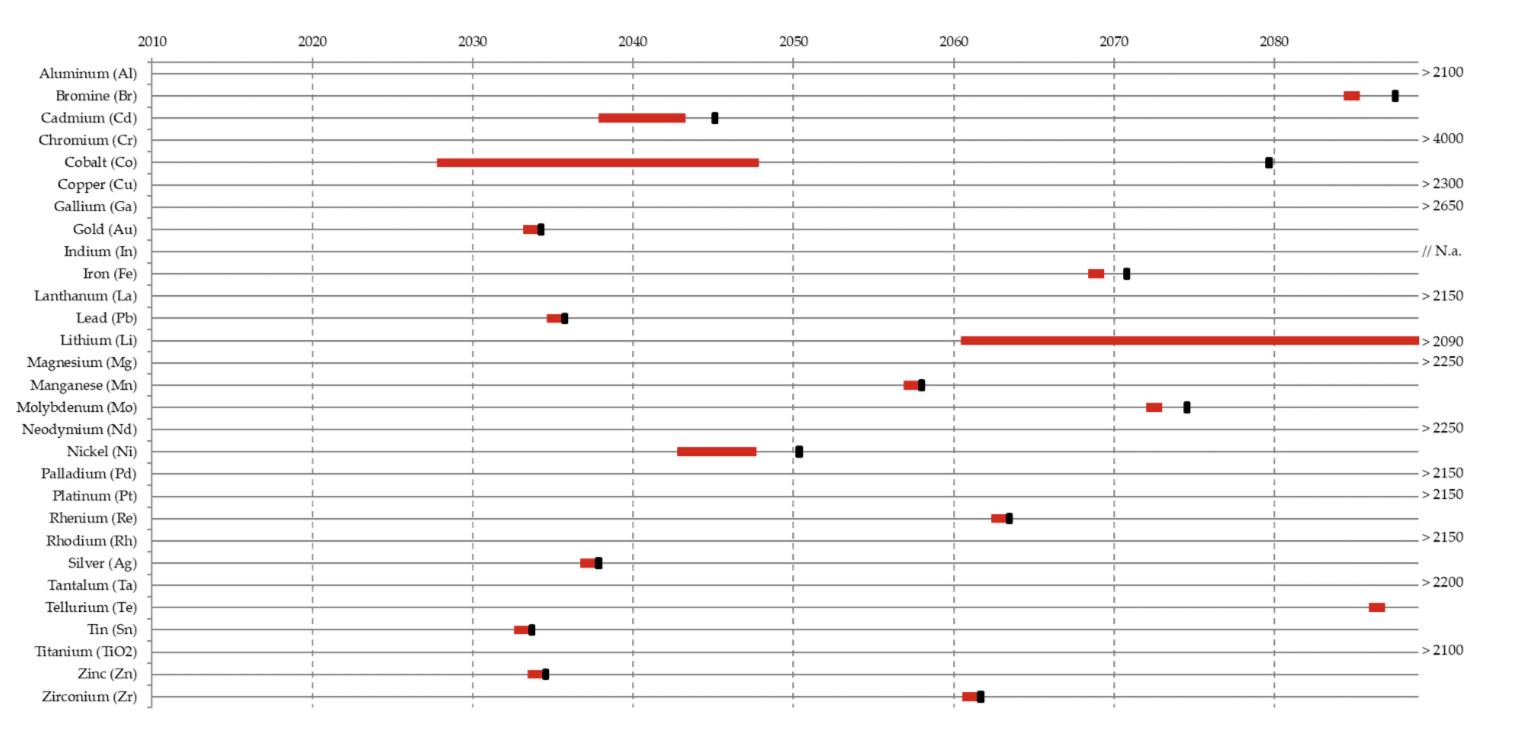

In a High VRE world, it is becoming recognised that low supply of rare earth and other raw materials could become a bottleneck to future deployment of some renewable technologies. The following figure, taken from Moreau, 2019, shows that eight metals (Cd, Co, Au, Pb, Ni, Ag, Sn, Zn) could be depleted before a High VRE system could be deployed at scale in 2050.

Cobalt and lithium are of concern in the manufacturing of batteries.

The GenCost assumes that increased and even extreme demand for PV solar and lithium batteries in the High VRE scenario simply causes PV solar and battery costs to fall and fall further. But the law of supply and demand suggests that as resources become scarce, the price should in fact increase. Similar considerations would apply to PV solar.

It appears that this has been completely overlooked in GenCost.

Battery prices and learning rates

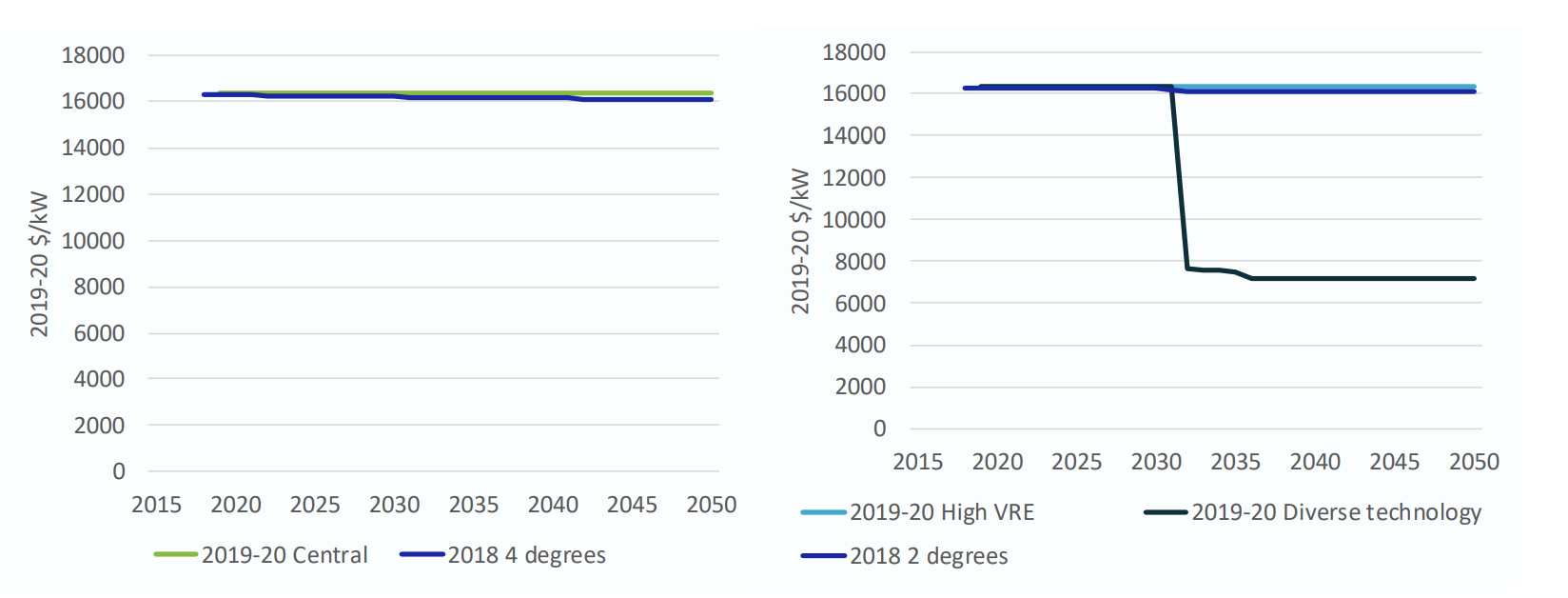

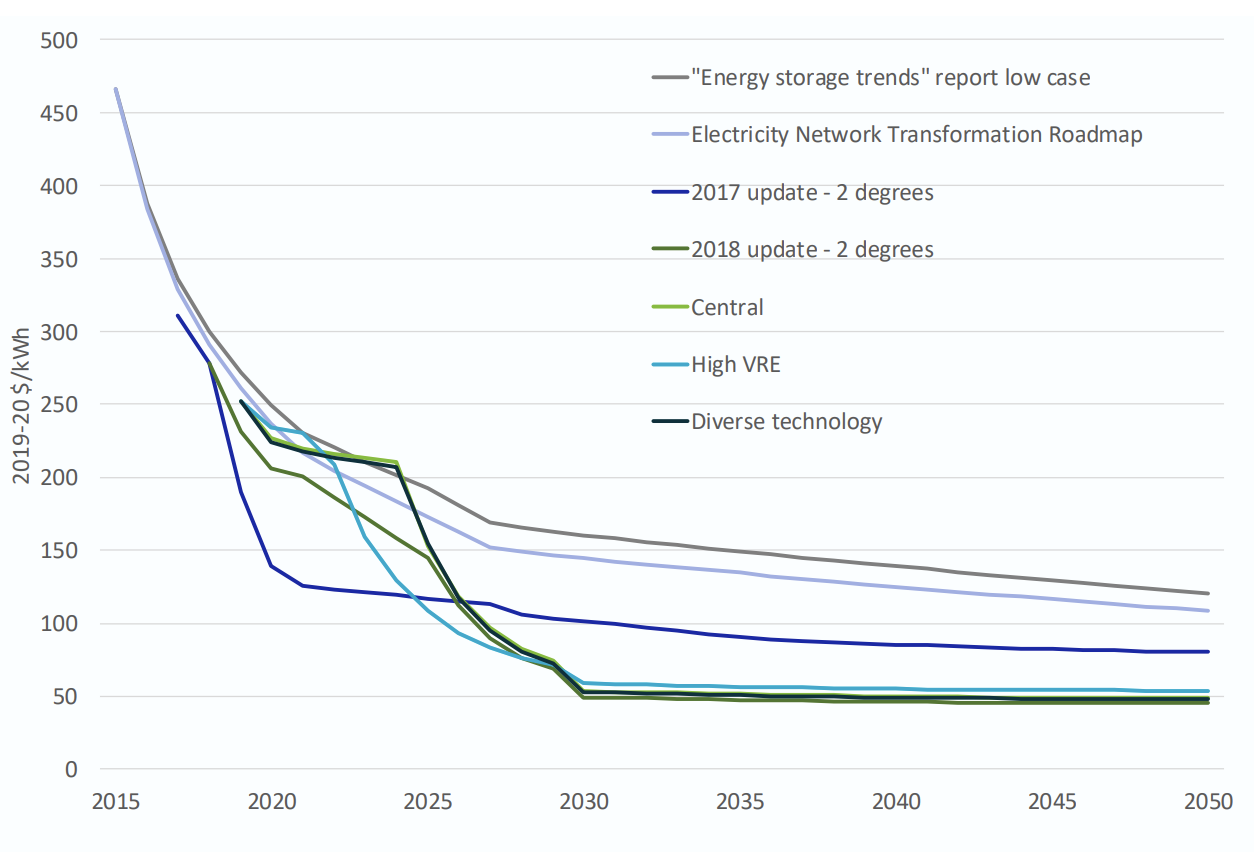

Rather than considering that high VRE and high electrification might lead to increased demand for scarce resources and higher prices, GenCost 2019-20 assumes the opposite, and once again provides a weak justification. The following is Fig. 3-13, p. 18:

In the text:

From 2018, CSIRO’s projection methodology recognised that battery technologies, while mature, are still experiencing learning rates more consistent with emerging technologies. As a result, we have allowed higher rates of learning to apply for longer periods than previous CSIRO studies. The outcome of this assumption is that battery costs achieve a lower cost of $50/kWh by 2050 compared to an average of $100/kWh in the pre-2018 projections.

It is also mentioned in the table on p. 8 that learning rates of “higher for longer in solar and batteries” are applied in High VRE and Central (although not in Diverse).

And just like that, the model halves the battery costs in 2050 compared to previous projections.

Summary

In this post I have discussed a number of troubling assumptions in the GenCost report, all of which appear to either bias cost projections of solar, wind and storage low, and/or bias SMR nuclear high.

References

- GenCost 2018, link.

- GenCost 2019-20 draft, link.

- Hayward & Graham, 2017, link.

- IPCC AR5 WGIII Ch 6, link.

- Inside SoftBank CEO’s vision for an Asia Super Grid, link.

- Diesendorf & Eliston, 2018, link.

- Moreau, 2019, link.

- Renew Economy, “New CSIRO, AEMO study confirms wind, solar and storage beat coal, gas and nuclear”, link.

1 Note there is much skepticism about China’s promised ETS, e.g. link.

tags: climate